Thinking, feeling, seeing

newness in oldness,

beauty in a soul laid bare,

freedom to embrace it all.

WHAT IS IT about old daguerreotypes, ambrotypes (collodion positives), and tintypes that still fascinates us nearly two hundred years after they were invented and replaced by more advanced technologies?

The daguerreotype was originally developed by early 19th century artists searching for a method to reproduce prints and drawings for lithography. The technique inadvertently contributed to the birth of photography, and we haven’t stopped taking pictures since – now more than ever before with the ubiquitousness of mobile technology.

But still, there is something arresting about antique portraits when we peer into the faces of people who are nothing more than strangers to us. The images have a certain depth and mystery that we rarely see in today’s fast-paced, social media, selfie-obsessed culture. So what’s the deal?

After much thinking on this, I finally realized a surprising truth that proves that technology shapes the content (and meaning) of creative expression. This happens because inherent physical and technological limitations have always determined the creative parameters and output of any technology. To use a modern example, the **selfie-stick expanded the previously limited photographic range of smartphones (from arm’s length selfies) to make it look like maybe somebody else took your picture and you’re not such a narcissist after all. Just kidding, but you get the picture.

Challenges in 1830s photography were different, but still had an effect on creative content. Long exposure times required the sitter(s) to keep very still while the plate was being exposed inside the camera. The process could take up to several minutes. Consequently, the body and facial expressions had to remain as still and relaxed as possible. Any movement, including blinking, would cause some amount of blurring in the photo. These types of poses were, out of necessity, the standard “look” of photographs at the time. But in analyzing this a little further, we observe a curious side-effect vis-a-vis content that completely transcends the physical or mechanical.

The effect that super-long exposure times had in portraiture was that it unwittingly dissolved the protective masks behind which humans conceal their inner lives. It peeled away the public persona we all unconsciously project to the outer world (think social media, where we carefully craft the best versions of ourselves). Like a microscope, it allowed the first cameras to peer inside the hearts and minds of husbands, wives, children, and others who had endured much – both good and bad. Nobody said “cheeeeese,” and without a practiced “camera face” camouflaging the features of these perpetually solemn people, we occasionally recognize in the photos a hint of something familiar – be it pride, bitterness, hardship, or whatever. We instantly know it by the set of the jaw, the tightness of the lips, or a twinkle in the eyes. There is nothing fake about the authenticity of these “leaked” emotions. In light of this knowledge, we should certainly be asking ourselves how modern technology is shaping content and meaning in our culture today, and how it may be affecting our values and habits.

I HAVE A CONFESSION to make. I’m not young anymore, and I’ve lived with depression for most of my life. When it comes on, it usually lasts for weeks and months at a time… and I don’t have a good poker face, if you know what I mean. On the positive side, I’ve learned to socialize more, rather than isolate like I used to, because it’s healthy and good for me (doctor’s orders.) My friends like to take a lot of photos when we’re together, which is usually fun. Anyway, (and this is the confession part) I’ve noticed in some photos a deep sadness etched across my face, especially in the eyes, and it’s almost too painful to look at. I thought this might be some unfortunate new development in my outward appearance, but oddly, it would appear that it was always the case (as you can tell by this professional portrait taken of me as a child the year of my father’s death). But then again, maybe it’s just that my adult mask has begun to dissolve as I transition slowly into a wise, but weathered crone. That might be it.

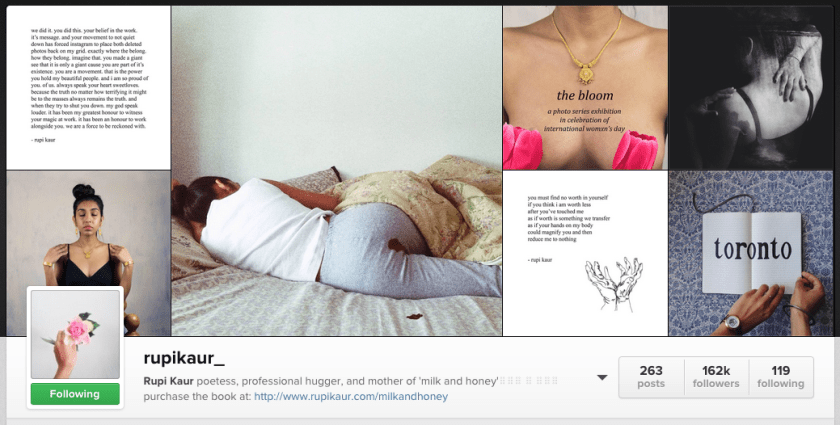

AS AN ARTIST, I’ve often used myself in my work because, well, I’m available 24/7, but mainly because my inner experience has always been the subject of my art – no matter the medium. Currently, I am using the Tintype Snappack from Hipstamatic to create pseudo-tintype photos, and creating double-exposure portraits as part of a new project. The combined effect of this medium + content is a good fit and creates exactly the right mood – honest and vulnerable in its naked truth. Stay tuned for updates.